A Vote for Women, A Voice for Change: Celebrating 100 Years of Women’s Suffrage

A girl watches the TV, its screen casting a blue light over her face. Her eyes brighten in amazement. The first Black and South Asian American woman to ever be nominated for vice president takes the stage. Senator Kamala Harris looks like her. The girl wonders if there will ever be a time when she will find a woman listed among the male presidents in her history books, let alone a woman of color. Maybe that will be her one day. For now, she listens and watches as Senator Harris takes part in the debate. She knows politics aren’t only for men anymore.

Women: the mothers, daughters and sisters, the unsung leaders of liberty and growth. In United States History, women’s efforts behind historic change are undermined to a truly unfortunate degree. Women did, and still do, reside under a male-centric government and education. Equality and representation on the basis of sex remains a pressing issue.

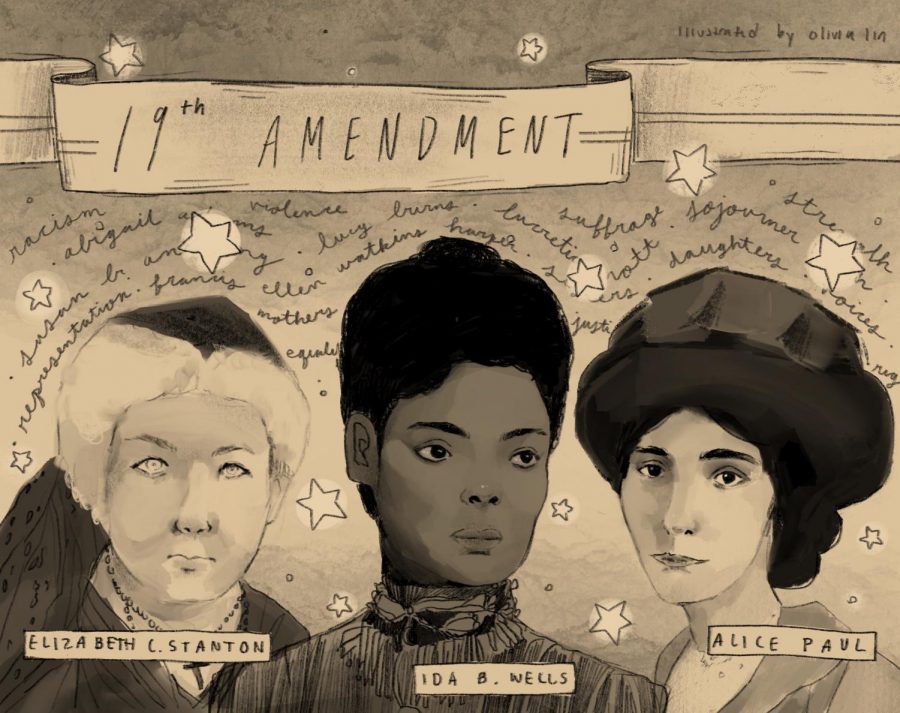

Even so, it would be flawed to not recognize the evolution of women’s rights leading into the 21st century. Women have come a long way since Abigail Adams first fought for women’s representation in legislation or when Sojourner Truth declared with fiery diction that women, of any race, should be treated as equals to men. This year, we commemorate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment to the United States Bill of Rights. A turbulent battle for voter equality, the Women’s Suffrage Movement came to a satisfying conclusion with the introduction of the 19th Amendment, one of the first pieces of legislation to recognize men and women as equal citizens.

A Brief History of the 19th Amendment

Alice Paul, Ida B. Wells, Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper; the list goes on. These women were integral advocates and leaders of the Women’s Suffrage Movement. They sacrificed their lives, reputations, and security for representation in government.

While the fight for equality among men and women has transpired in many timelines, the focus on suffrage can be traced back to the early 19th century. In 1840, women were excluded from attending the World Anti-Slavery Convention held in London, prompting Elizabeth Stanton and Lucretia Mott to hold a Women’s Convention in the US. Elizabeth Stanton was a white author, lecturer, and philosopher. Lucretia Mott, a white abolitionist and founder of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Together, they discussed abolition and women’s roles in their current society and got to work.

The first ever Women’s Rights Convention occurred in Seneca Falls, New York on July 20th of 1848. There, Stanton wrote the agenda for women’s activism titled “The Declaration of Sentiments.” A strong metaphorical message, Stanton paralleled the fight for independence led by the Founding Fathers to the Women’s Rights Movement. 68 women and 32 men signed the document that day. The Seneca Falls Convention marks the very beginning of a long, and strenuous battle.

A defining moment at a Convention in Akron, Ohio, Sojourner Truth, abolitionist, women’s activist, and former slave, delivered the powerful “Ain’t I a Woman” speech in 1851. She criticized the treatment of women, especially Black women, in the US as subordinates to men. In her speech, she declares “If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it. The men better let them.” Truth was a vital leader in women’s rights, and, as seen in her work, was a faithful woman who used religion to promote the inclusion of women who were frequently brought down by their faith.

Numerous suffragettes remained single in 1868 in defiance of the laws that denied women the right to make legal contracts on their own behalf and own property. At this point in time, the 14th Amendment was ratified with “Citizens” and “voters” being defined as only men.

In 1869, the formation of women’s suffrage associations came to fruition. Stanton and Susan B. Anthony created the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) based in New York. The NWSA focused on Constitutional revision, a more radical institution than its more conservative counterpart, the AWSA. The American Woman Suffrage Association was formed by suffragists Lucy Stone, Henry Blackwell, and Julia Ward Howe and aimed towards amending individual state law. These two groups eventually consolidate, forming the National American Women Suffrage Association. The National Council of Women in the United States is another association introduced two years later, in 1890.

From the years 1893 to 1918, states slowly, but surely, adopted woman suffrage. It was not until 1919 that that began to change.

It was on May 21st, 1919 that the House of Representatives passed the 19th Amendment, followed by the Senate’s approval on June 4th that same year. On August 18, 1920, once Tennessee, the last state to ratify the amendment, did so accordingly, the 19th Amendment was officially adopted by the United States Legislature. This marks the moment in which women were granted the right to vote, ending nearly a century of toiling protest. It remains a promise to this day, a guaranteed right, that no voter may be discriminated against on the basis of sex.

Literal Blood, Sweat, and Tears

Violence is a part of the journey towards suffrage that is widely disregarded. Led by Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party, a group of women coined the Silent Sentinels picketed outside the premises of the White House every day during Woodrow Wilson’s presidency. This endeavor began on January 10th of 1917. Their tranquil protests, though initially met with indifference, were interrupted by violence during the wartime fervor of WWI. Their protests were thought of as outrageously unpatriotic. In June, the police began arresting the women. They were sent to jail, oftentimes released quickly. However, to the police’s dismay, they kept coming back. By August, tensions aggressively rose as angry mobs and police attacked the women. The stakes of imprisonment heightened. Paul was arrested that October and sentenced to seven months in Occoquan. There, she was tortured. Paul voluntarily went on a hunger strike while sent away, and in response was force-fed worm-ridden food and given filthy water and bedding. When November came, she was transferred to the District jail’s psychiatric ward.

On the night of November 14th, 1917, thirty-three women were put under arrest and brought to the Occoquan Workhouse. Alike to Alice Paul, the women demanded to be treated as political prisoners; however, they faced a brutal evening of physical assault that would come to be known as “The Night of Terror.” Guards dragged the women to dark, filthy jail cells. By the orders of prison superintendent William Whittaker, the women were to be “taught a lesson.” Suffragist Lucy Burns was forced to stand all night, hands shackled to the top of the cell. Dorothy Day, frequently described as a frail girl, was slammed down onto an iron bench twice. And Dora Lewis had her head smashed into an iron bed, making her lose consciousness and sending Alice Cosu to suffer from a heart attack after witnessing her friend’s assault.

Following these events, the women began conducting hunger strikes. Whittaker sent the U.S. Marines to guard the workhouse where the women suffered until late November when news of the abuse reached suffragists outside of Occoquan. The women managed to bring the case to court and the D.C. The Court of Appeals deemed the acts of arrest, conviction, and imprisonment as illegal. Despite experiencing such a harrowing experience, the hunger strikes, picketing, and arrests continued.

“The Night of Terror” and the physical strife of Silent Sentinels stand as symbols of strength and the courage it took to gain representation in the US government.

A Racial Divide

The Women’s Suffrage Movement is closely linked to the Abolitionist Movement. In this post- American Civil War society, Black men and women spoke out against the prejudices and racism they faced as American citizens. Black women brought an essential perspective to the Women’s Suffrage Movement as they truly understood what it mean to be a minority because of one’s race AND sex. However, just because most women’s rights activists were duly abolitionists, it does not necessarily mean that they supported the voting rights of ALL citizens.

It would ignorant to avoid the topic of racism towards non-white suffragists. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, one of the most influential leaders of this movement, was an infamous racist. Ironically, her husband, Harry Stanton, a well-known abolitionist at the time, was against the 15th Amendment. Stanton was unfortunately not an advocate for all women, having betrayed the interest of her Black suffragette counterparts.

She, along with Susan B. Anthony, generated tension between white women, and Black women and men after refusing to support the ratification of the 15th Amendment, which granted Black men the right to vote. Anthony and Stanton were furious that men of another race gained suffrage before white women. Their fury remained even with the support of Abolitionist and Suffragist Frederick Douglas who bolstered the idea that a vote for a Black man was one step closer to women’s suffrage. Anthony and Stanton’s attitudes and the racial tension that stemmed from this ultimately caused the dissolution of AERA, American Equal Rights Association, which they created with Douglas.

In a New York Time article titled “How the Suffrage Movement Betrayed Black Women,” writer Brent Staples deems that the written history of women’s suffrage “rendered nearly invisible the black women who labored in the suffragist vineyard and that it looked away from the racism that tightened its grip on the fight for the women’s vote in the years after the Civil War.” These words capture what hindered the movement: racism. If white and Black women were fighting for the same right, it can be argued and supported that the movement could have been far more productive if they worked in unison.

A blatant example of the lack of inclusion of Black women in the suffragist movement that Staples depicts is a Washington parade in 1913 in which all Black participants were forced to walk in the back of the parade, away from the white suffragists. Suffragist, accomplished journalist, and Civil Rights leader Ida B. Wells refused. She knew that she deserved to be at the front of the parade, especially as an individual who was a prominent figure of the movement.

This divide never truly vanishes, as seen in modern society with Black women being treated with less respect and attentiveness than white women when receiving medical attention, applying for work, and seeking higher education. According to a 2016 study from the CDC (Center for Disease Control and Protection), the pregnancy-related deaths for Black women over 30 were four to five times higher than that of white women as a result of insufficient healthcare because of racial biases. The education level of the women had no effect on these numbers, with Black women, who all had at least a college degree, were around 5.2 times more likely to die in pregnancy than white women.

Black women were treated, and still are, as a minority among minorities.

To Vote or Not to Vote: Utilize Your Right

As tension has risen in the political environment, so has anger among younger generations of voters. Who do we trust? Will political leaders elected into office protect our rights? The honest truth; nothing is guaranteed. Simply, how will we know what we can become if we never try in the first place? By exercising our right to vote as citizens of the United States, we stand for the freedom of speech and expression that women, and men, fought so fervently for. Before the Election, consider the suffragists. You may be one US voter out of 328.2 million citizens, but your voice matters!

This is Just the Beginning

Women have come a long way to where we stand as contributing citizens in the US today. We have lived to witness a major political party, for the first time ever, nominate a female presidential candidate. And in 2020, more women than ever before have ran for president. We have also had to mourn the loss of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a voice for women’s litigation who brought gender inequality matters to the forefront of judicial law. Ginsburg’s legacy reminds us of the vigor each one of us possesses.

The journey to true equality persists. And with unity and perseverance, it can be possible. If there is anything to take away from the Women’s Suffrage Movement it is that women are strong, and even stronger when we stand together in appreciation of all races, ethnicities, backgrounds, and beliefs. And truthfully, the US would benefit from men and women working together, equals in work, opportunity, leadership, and respect.

Remember your suffragists at the polling booth. What future do you want to see?