Hills 50 Years Ago: Continued

The “Nebbish”

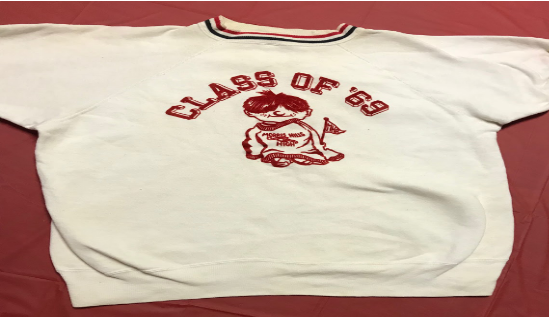

The senior sweater is a familiar sight to most Hills students; in recent years, it’s known for having the signatures of the senior class in the shape of the graduation year.

In 1969, the senior sweater was designed by a student and featured a Hills fan carrying a pendant.

Both sweaters, made 50 years apart, are pictured below.

America Fifty Years Ago

By the time the school year started at Morris Hills in September 1969, students had seen things they could never have imagined. In that year alone, man landed on the moon for the first time, hundreds of thousands crowded upstate New York to attend the Woodstock music festival, and the United States entered its fourth year in the Vietnam War. It was a time of change and polarization. Ultimately, the year and the era it belonged to would be defined by young people’s response to this change, known as the youth counterculture.

For many, the state of affairs justified such strong protest. Prior to 1969, the majority of the men who went to serve in the Vietnam War were of lower socioeconomic classes, because those in college were legally exempted from fighting, and those who had the necessary connections could avoid it through other means. The public began to criticize the draft process, forcing the government to find another way to build the military. The solution was draft lotteries, first seen in 1969, where birthdays were picked from a glass bowl and given a number. For example, the date September 14th was chosen first and given the number one. Young men age 19 or older with that birthday would be drafted first.

For teens today, the scene may be reminiscent of The Hunger Games, where the people anxiously waited to hear if their name would be called and they would be sent to danger. Though it closely resembles today’s fiction, the draft lotteries of the 60s and 70s were anything but.

Hills students, particularly members of the Hilltopper, did not stay silent on these issues. October 15th, 1969 saw a nationwide protest against the war, known as Moratorium Day. Morris Hills participated by hosting a debate on whether or not the United States should withdraw from Vietnam. A reflection on the debate in the October edition of the Hilltopper commended the administration for acknowledging the war, directly requesting that they “don’t stop after one success” and continue to encourage the expression of political views.

In the months following Moratorium Day, the Hilltopper became a vessel for students to share opinions on the war and politics. That November, a student wrote about his experience watching one and half million people attend an antiwar demonstration in Washington, D.C.: “It was the most beautiful scene I ever saw.” Another student writer criticized President Nixon for “the facts left out” of his famous “silent majority” speech.

The next month, a letter to the editor expressed pro-war sentiments, arguing that the Hilltopper’s coverage was biased and only showed the opinions of the “verbose minority.”

The line that divided the nation in 1969 divided Morris Hills as well. While the free expression of opinions on the war sometimes caused controversy, it also allowed the teenagers of the 60s some agency over a world that was for the most part out of their hands. In editions of the Hilltopper from 1969, readers can witness a generation discovering its voice and recognizing that debating the issue was the first step in fixing the issue.

Fifty years later, the landscape has changed, but many of the sentiments haven’t. Adolescents today have grown up in a society plagued by problems of every variety, from student debt to political polarization to a government that sometimes seems indifferent to teenagers’ problems. Like teens of the 60s, they’ve taken matters into their own hands. 2017 saw the March for Our Lives, where young people around the country came out to protest gun laws, and in 2019 hundreds skipped school to demand action in regards to climate change.

Despite half a century between them, these two generations have one strong uniting factor: when faced with fear, they act.

With the future full of disheartening inevitabilities, it’s powerful to look back and see how adolescents faced challenges fifty years ago. The students of 1969 discussed the issues, listened to the arguments, and demanded that the school and the country recognized the importance of what they were saying. They managed not only to make it through high school, but to also create a better world in which to live. With luck, and with that quintessential teenage spark of rebellion, the Hills students of today will too.

Dress Codes, Then and Now

In recent years, dress codes have been seen as not only inconvenient but also unfair, limiting student expression with rules that can feel arbitrary.

Fifty years ago, this statement was still true. The rules in question, however, were far more strict.

Boys could not wear sneakers or jeans, and their sideburns could not extend past half the ear. Girls were only allowed to wear skirts or dresses, and the hems had to go just past the knee. There was one day a year in which senior girls could wear pants.

The Hills alumni present at the reunion remembered the dress codes well- more specifically, how those codes were ignored.

Bruce Harris, who went to Morris Hills for three years, remembered his friends being particularly upset about the rules on sideburn length. “They decided they would grow their sideburns long so they grew them to the bottom of their ear.” he said. “The administration didn’t do anything, but some of the kids in the school called them out and shaved them themselves.”

In other cases, the administration played a greater role in enforcing the dress code. “The last day of school in June I came in with white Levis.” recalled Pamela Budd, a ‘69 graduate. “I was sent home.”

Cases like these represent a greater dissatisfaction on the part of the student body with the codes. In the December 1969 edition of the Hilltopper, the Student Government Association announced the results of its poll, which asked students what they thought the new dress code should be. Some answers might seem like a given to students today- for example, both boys and girls requested the freedom to wear blue jeans. Others, despite being written by teenagers, would appear strict to the modern student. The list of restrictions includes rules like “plain white t-shirts may not be worn” and “hair (including moustaches, beards, goatees, sideburns) must be neat and well-groomed.”

It appears that every generation brings with it new standards for dressing, with new definitions of appropriate and inappropriate. Though the students of 1969 may not have seen changes to the dress code in their four years at Hills, their hopes of more lenient restrictions were eventually realized. A schoolwide effort today to change the dress code may follow a similar pattern- perhaps the changes happen slowly, but they do happen.

Sports Night

It’s a tradition that no longer exists at Hills, but one that certainly left an impact on the class of 1969: Sports Night.

Part competition, part variety show, Sports Night was a way for every girl at Morris Hills High School to show her talents. Female students of all grades were put on either the Scarlet team or the White team, in honor of school colors.

Each team had its captains and committee heads. These students were in charge of choosing a theme for their show and rallying their side. Pulling it off was no small feat: both the Scarlet and White teams would create spectacles with dances, gymnastics, and skits.

The girls who didn’t wish to dance participated in other ways, like helping create the elaborate sets that went with the show. With everyone contributing their strengths, Sports Night was truly a united effort.

All this effort, however, did not directly benefit the girls who put in the work. Instead, the money made with Sports Night went to support Morris Hills’ boys-only athletic program.

Despite this, former students look back on the event fondly.

“It was phenomenal,” said Robin Rath, who also noted the event’s popularity. “Everyone wanted to come to it.”

Today, many of the creative endeavors that Sports Night required can be seen in other school programs, such as color guard, cheerleading, and theater. Not since the 1980s have these talents been seen all in one show, as a grand tribute to what Hills students have to offer.

For the alumni at the reunion, Sports Night helped shape their memories of high school. Unfortunately, however, most students today have never heard of the event. Celebrations that used to define life at Hills are now forgotten, buried under five decades’ worth of yearbooks and newspapers. Looking back on the events of the past not only offers a whole new world to explore, but also ensures that the efforts and joys of that time are not lost.